THE LONG VISION QUEST

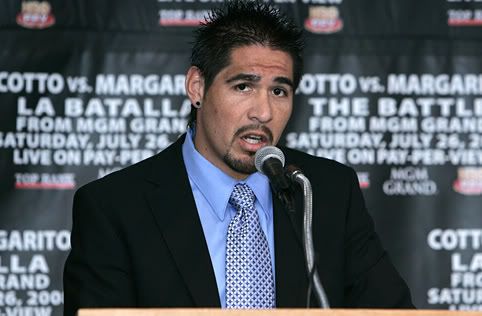

It took Antonio Margarito six years to find an elite boxer willing to fight him. Now that he has one in Miguel Cotto, Margarito is so intensely focused that his manager put up a big TV screen in the gym playing nothing but nonstop Cotto fights.

by Nat Gottlieb

For the longest time, Antonio Margarito must have felt like the flip side of Rodney Dangerfield: He got too much respect. His promoter, Bob Arum, smartly exploited this problem by coining a mantra he would repeat whenever somebody seemingly ducked his fighter: "Antonio Margarito is the most feared fighter on the planet today."

Arum's words transformed Margarito's public image from a champion who had fought nobody of great consequence to a de facto elite fighter. Margarito wasn't the first fighter nobody seemed to want to face, and he certainly won't be the last. Winky Wright knows a thing or two about being avoided. But in Wright's case, his defensive style of fighting was hard to sell, and it was difficult to look good against him. The opposite is true with Margarito.

His manager, Sergio Diaz Jr. knew he had a Mexican fighter with a crowd-pleasing, all-action attack. It seemed like a natural sell, and that's what made all the years waiting in the wings for a big show so difficult.

"It's been frustrating to myself and Antonio because of the type of fighter he is," said Diaz, who has been with Margarito for 12 years. "He likes to fight for the fans, to put on a show. He's always thinking about the fans, so struggling to get a lucrative offer against a top fighter has bothered him because he wants to please the fans with the best fight possible."

Margarito found himself stuck in the worst kind of boxing Catch-22: He was a high-risk, low-yield fighter, meaning he hadn't fought any big name boxers, so he didn't bring much money to the table. But how could Margarito get an elite boxer on his resume if none of them wanted to fight him?

Even more perplexing was that Margarito wasn't some wannabe contender. He won his welterweight title in 2002 by beating Antonio Diaz and then successfully defended it eight straight times. But not one of those opponents could remotely have been called elite, and as a result, Margarito continued to fly under the money radar despite being a long-reigning champion. The closest Margarito came to facing a big name was in Kermit Cintron, a red-hot contender in 2005 whom he knocked out in five rounds.

What did that important victory bring Margarito? How about a title defense against one Manuel Gomez, who had a very undistinguished record of 28-10-2. It was obvious that by laying some serious hurt on the highly-regarded Cintron, Margarito had only wedged himself deeper into his Catch-22 box. He looked riskier than ever.

Shane Mosley was on the same card with Margarito-Cintron, beating David Estrada in the co-main event. Diaz and Top Rank thought the pairing of the two winners would be a natural, so Diaz says Top Rank made Mosley a lucrative offer. Instead of taking it, Mosley chose Jose Luis Cruz for his next fight, a boxer with a record of 33-0-2 heavily padded with non-entities in Mexico. How did Margarito stay focused through all those tough years? "We kept telling him your time will come, keep winning and let people see your face," Diaz said.

The manager discovered Margarito by accident. In 1996, Diaz went to watch a rising contender and future world title challenger named Rodney Jones, who was fighting Margarito. At the time, Margarito was an unknown boxer fresh out of Mexico with two losses in just 11 fights. Jones must have figured it would be a soft fight -- and he did win by unanimous decision -- but it was a hard-fought bout. Diaz was impressed more with Margarito than Jones. "I didn't even know who Tony was," Diaz said. "But after the fight I said, 'Wow, this guy can really punch and has a chin.'"

Diaz checked out Margarito's record more closely, and it became apparent why he had two losses. "They came before he was 19," Diaz said. "He was a child fighting men."

In his sixth fight at age 16, Margarito lost to Victor Lozoya, who was three years older. When Margarito was 18, his second loss was handed to him by an unbeaten 28-year-old named Larry Dixon. Jones, who was also 28, gave Margarito his third loss. At 9-3, Margarito did not look like a top prospect.

"Having those three losses made it much more difficult for us to find a promoter," Diaz said. "We begged people. Finally I talked to (Top Rank President) Todd DuBoef, and he said to bring him down to his office and we would get a deal done."

Part of Margarito's past problems in landing an elite fighter could be blamed on him simply being in the right place at the wrong time. Margarito was still a rising prospect when the welterweight division had names like Oscar De La Hoya, Mosley, Felix Trinidad, Vernon Forrest and Ricardo Mayorga. By the time Margarito had established himself, all of them except Mosley had moved up to junior middleweight. Mosley actually had already been fighting at 154 and had only dropped down for two welterweight fights before going back up.

Margarito was so desperate for a big fight that he himself moved up to 154 pounds to challenge title holder Daniel Santos. It proved to be a disaster. In the 10th round of a close fight, Margarito suffered a gash over his right eye from an accidental head butt, and it was bad enough for referee Luis Pabon to halt the fight and go to the scorecards. Margarito was ahead on one card, 86-85, but Santos had the edge on two others, 86-85 and 87-84. As a result Margarito suffered his first loss in eight years, breaking a string of 20 straight victories.

"After losing to Santos, our team was all down, but not Tony. He smiled and told us to keep our heads up and he'll become champion again," Diaz said.

Margarito moved back to welterweight and immediately won a championship. The division, meanwhile, was starting to look up again as both Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Zab Judah moved up from junior welterweight.

Both of those fighters, however, avoided Margarito like the proverbial plague. Judah was a champion in 2006, but rather than fight Margarito and unify titles, he chose a little-known Colombian who was on a long winning streak, Carlos Baldomir. When Baldomir upset Judah, he too chose to bypass the high-risk, low-yield Margarito, fighting instead Arturo Gatti, who was guaranteed to bring in a full house in Atlantic City.

As for Mayweather, it has been well chronicled that he turned down an offer of $8 million from Top Rank to face Margarito. Arum tried every trick in the book to lure Mayweather into the ring, carrying on a year-long campaign. Instead, Mayweather took fights less challenging and for smaller money against Sharmba Mitchell, Judah and Baldomir before he hit the jackpot last year with De La Hoya, and then again with blown-up junior welterweight Ricky Hatton.

The long ordeal for Margarito was made harder to swallow as he watched Top Rank turn Cotto into a star. Diaz has frequently inferred that part of the blame for Margarito's problems could be laid at Top Rank's doorstep, although it should be noted he re-signed with them last year.

While Cotto has been kept busy earning money for himself and Top Rank, Margarito has barely been active in comparison. Starting in 2001, Margarito has fought only twice in every year through 2007. In contrast, when Cotto won his first championship in 2004, he fought four times that year, and three times each in 2005-2007.

Margarito seemed poised to finally get his big fight when Arum penciled him in to face Cotto in June of 2006. But to do so, Margarito would have had to give up his championship belt because he had a mandatory ordered with Paul Williams. But Margarito is one of those increasingly rare fighters who actually cherish their belts, so he chose to fight Williams for what was then his highest purse, $1 million, but several hundred thousand dollars less than he would have gotten against Cotto that June.

The result was that Margarito lost his belt to Williams in a tight unanimous decision, 113-115 twice, and 112-116. "Tony started too slow," Diaz said. "But I'm not making any excuses. Williams won because he threw more punches, although those punches didn't land that much and they weren't as hard as the ones Tony was throwing and connecting with. Once Tony got inside, the fight turned around, but it was too late."

Fate, which has never been all that kind to Margarito, also conspired against him in the Williams fight. Diaz was told Margarito would have 40 minutes to warm up, but two preliminary fights resulted in quick knockouts. Margarito was still wrapping his hands when he was informed to get ready, just 10 minutes from the opening bell. "Tony never got a chance to really warm up, which is why he had that slow start," Diaz said.

The resilient, ever-optimistic Margarito won a tune-up against Golden Johnson and then knocked out Cintron again, who was by now a reigning champion. With his impressive victory over Cintron, and his belt back, Cotto-Margarito become a viable fight again for Top Rank.

Diaz and Margarito are well aware of the stakes in this fight with Cotto, a universally recognized elite boxer. "I believe Tony will beat Cotto," Diaz said. "If he does, then people will start calling him out."

With Mayweather having retired, if Margarito wins Arum could narrow his mantra and call him "the most feared welterweight on the planet." The only difference this time is he won't be the most avoided.